Assessment is an important topic in education, with teachers, administrators, parents, students, and policymakers all staking a claim to the results of various types of assessments (NWEA, 2015).

Assessment can be used to inform teaching and provide feedback to students. When used effectively, it can “support and enhance learning” (Shepard, 2000, p. 4).

Testing is just one form of assessment. Drawing by Sarah Van Loo, 2017.

In an effort to improve my assessment practices, I critically examined one of my own assessments. First, I chose three elements that “make it possible for assessment to be used as part of the learning process” (Shepard, 2000, p. 10). Then I began drafting a rubric with which to assess other assessments, Rubric 1.0. As the name implies, this rubric is a work-in-progress.

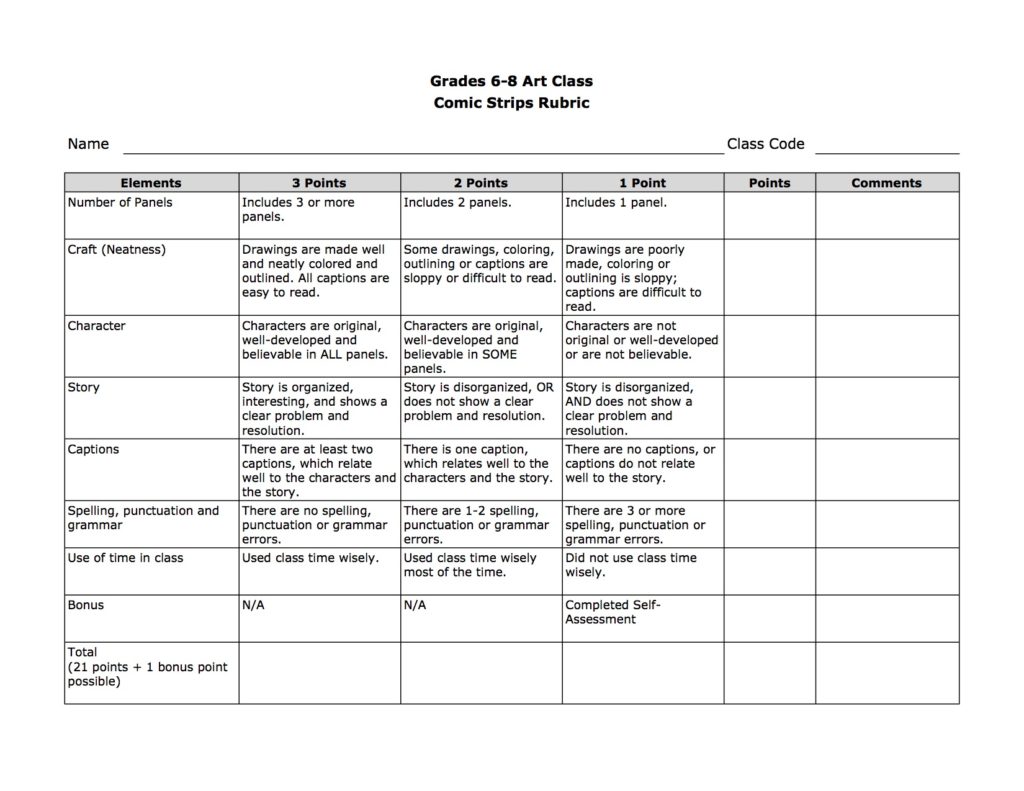

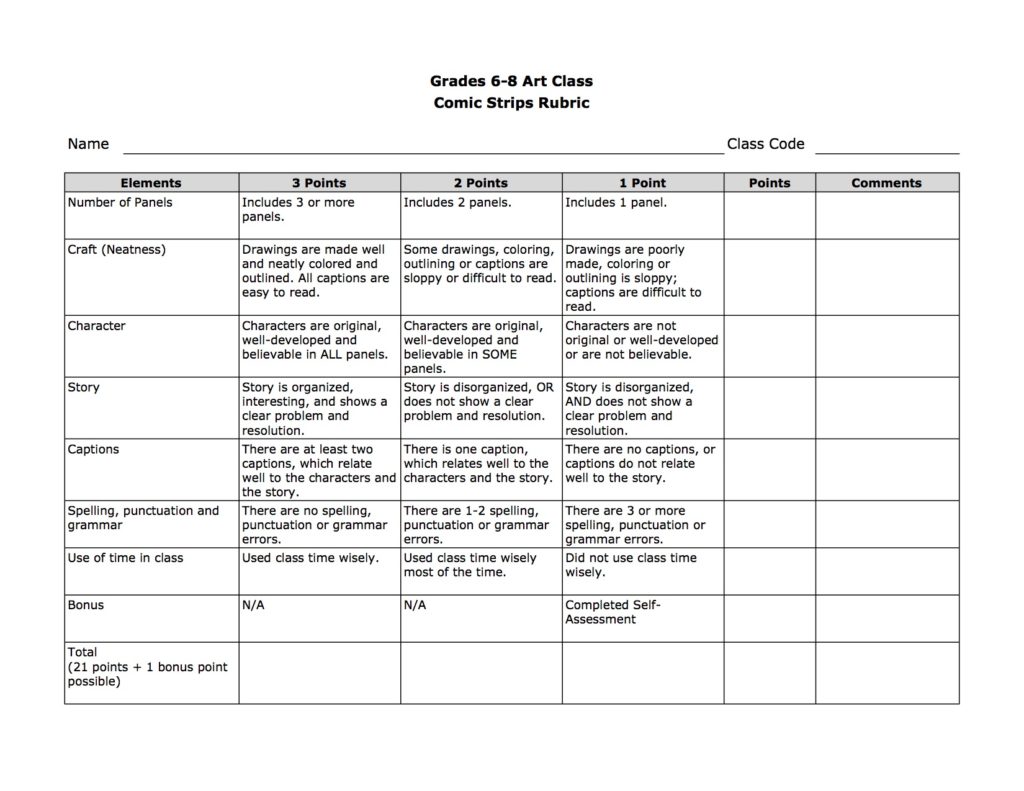

Rubric for an Art Project

The word assessment can refer to both the instrument and the process (MAEA, n.d.). The assessment tool that I chose to examine is a rubric for a comic strip. The last time I used this assessment tool was a few years ago. Nevertheless, I created it using a format that I often use for middle school art rubrics, so I think it is useful to examine it.

The assessment process was a project, the creation of a comic strip by each student in my middle school art class. The purpose of this assessment was to evaluate students’ understanding of craft, character development, story, and the basic elements of a comic strip, through their creation of a comic strip.

The assessment process was a project, the creation of a comic strip by each student in my middle school art class. The purpose of this assessment was to evaluate students’ understanding of craft, character development, story, and the basic elements of a comic strip, through their creation of a comic strip.

When I created this assessment tool, I made the assumption that my students were able to read and interpret each of the criteria and descriptions. I also made the assumption that my students understood the vocabulary used in the assessment tool.

Examination of My Comic Strip Rubric

Assessment doesn’t have to be a monster. Drawing by Sarah Van Loo, 2017.

In examining my rubric, I assessed whether it met the three criteria I used to create Rubric 1.0: feedback to students is direct and specific, learning targets are transparent, and it includes a component of self-assessment by the student.

Feedback to Students is Direct and Specific

According to Black and Wiliam (1998), feedback to students should be direct and specific, giving advice to students so they know what can be improved. This helps students recognize their own ability to improve.

In my experience, students sometimes view themselves as “talented” or “not talented.” With specific feedback about their own performance, they develop a growth mindset and learn that they can improve regardless of where they started.

The comments section of my assessment tool provides a space to provide specific feedback to students. If the teacher does not use the comments section but only circles the pre-written descriptions, students may view this feedback as vague.

Learning Targets are Transparent

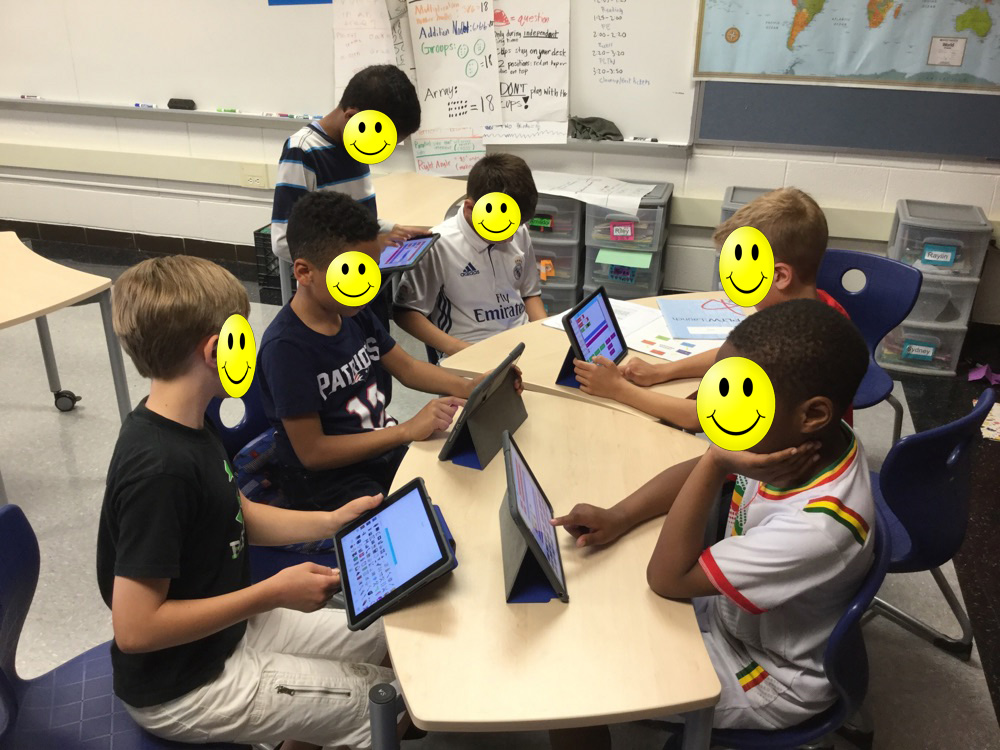

Students should have access to the criteria by which they will be graded, providing them with the opportunity to strive for excellence and the ability to see the “overarching rationale” of classroom teaching (Black & Wiliam, 1998, p. 143).

I have noticed that when students have clear expectations laid out for them, it prevents a lot of questions from being asked. Students do not need to ask or guess what quality work looks like because clear guidelines have already been established.

The comic strip rubric sets forth clear expectations for quality of work, quantity of work, and use of time in class. It is possible that more elements of a good comic strip could be added, but this rubric sets forth standards for excellent work, as well as work that could be improved.

Includes a Component of Self-Assessment by The Student

When students assess their own work, the criteria of the assignment and feedback from others becomes more important than the grade alone. Students who assess their own work usually become very honest about it and are prepared to defend their work with evidence (Shepard, 2000).

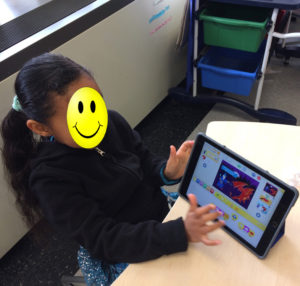

Students who assess their own work are prepared to defend their work with evidence.

When students assess their own work, they use what they discover to improve their own work. I have noticed that they iterate on their projects and make improvements, without prompting.

The comic strip rubric allows for student self-assessment, providing one bonus point for doing it. In my experience, this provides an incentive for some students. Other students do not see the inherent value and therefore pass on assessing themselves. Rather than making it an optional bonus point, it could be a required element of the rubric.

Conclusion

At this point, the comic strip rubric does include the elements of Rubric 1.0. As I revise Rubric 1.0, though, I expect to discover ways to improve my comic strip rubric.

REFERENCES

Black, P. & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139-144.

MAEA. (n.d.). CEP 813 module 1.1 introduction. Retrieved from https://d2l.msu.edu/d2l/le/content/585048/viewContent/5241064/View

NWEA. (2015). Assessment purpose. Retrieved from https://assessmentliteracy.org/understand/assessment-purpose/

Shepard, L. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29(7), 4-14.