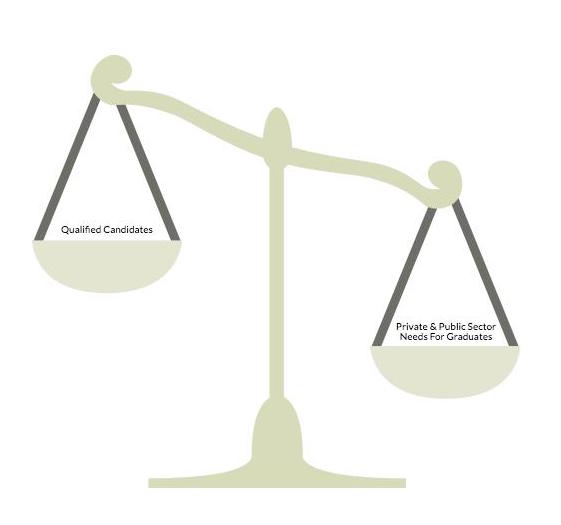

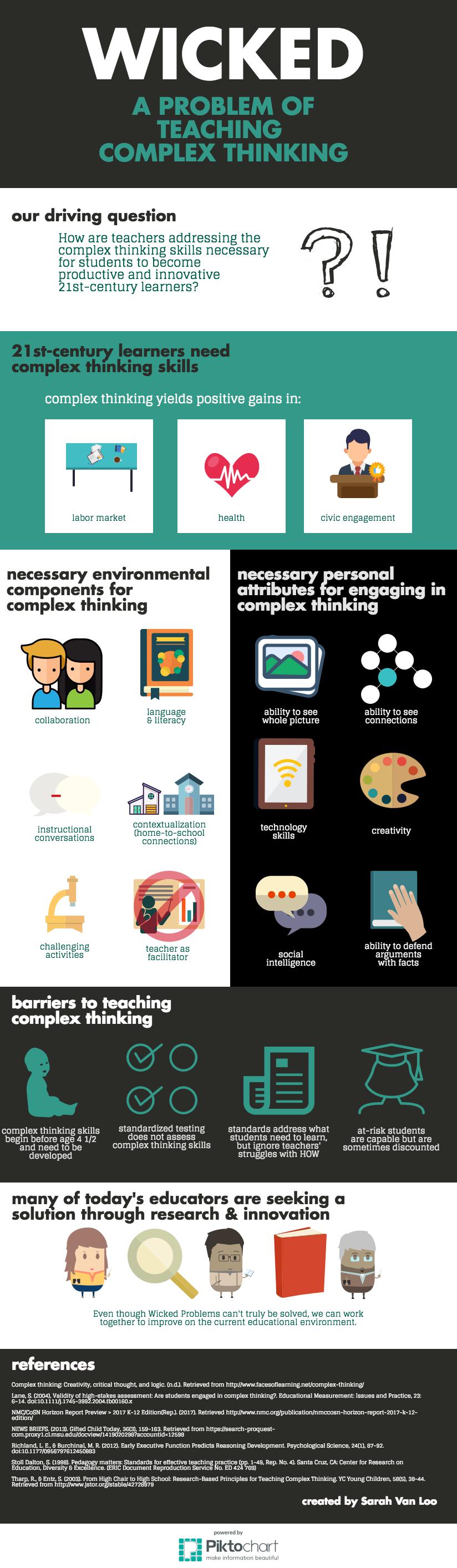

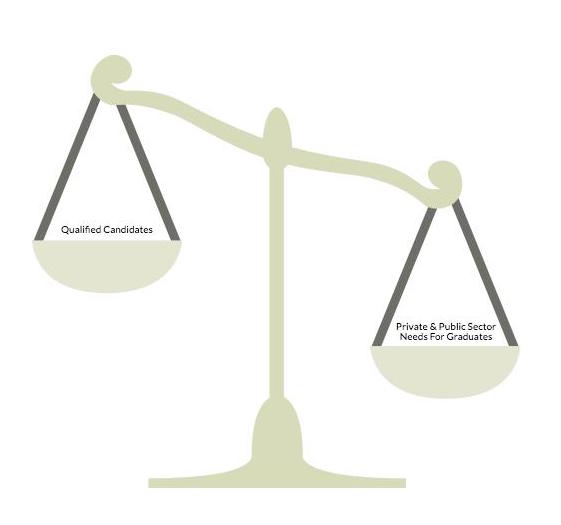

Today’s workforce requires graduates with 21st-century skills of collaboration, communication, creativity, and critical thinking, as well as entrepreneurship and innovation. These skills are needed in both the private and public sectors, but many of today’s graduates don’t have them (Jolly, 2016).

Today’s graduates are not qualified to fill many tech positions in the public and private sectors.

Hoping to solve this problem, a new movement focuses on educating students in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). Yet even with continuing unemployment, many tech companies are still unable to find graduates with the 21-century skills they need (Jolly, 2016).

STEAM: Today’s Answer to STEM?

We need innovators and creative thinkers to help transform our economy. In the 20th-century, that transformation came about through science and technology. In this century it’s art and design that are poised to help facilitate that change (“STEM to STEAM”, n.d.).

This understanding has fostered the STEAM education movement, which adds art, design, and the humanities to the four STEM subjects (Johnson Becker, Estrada, & Freeman, 2015).

Why STEAM?

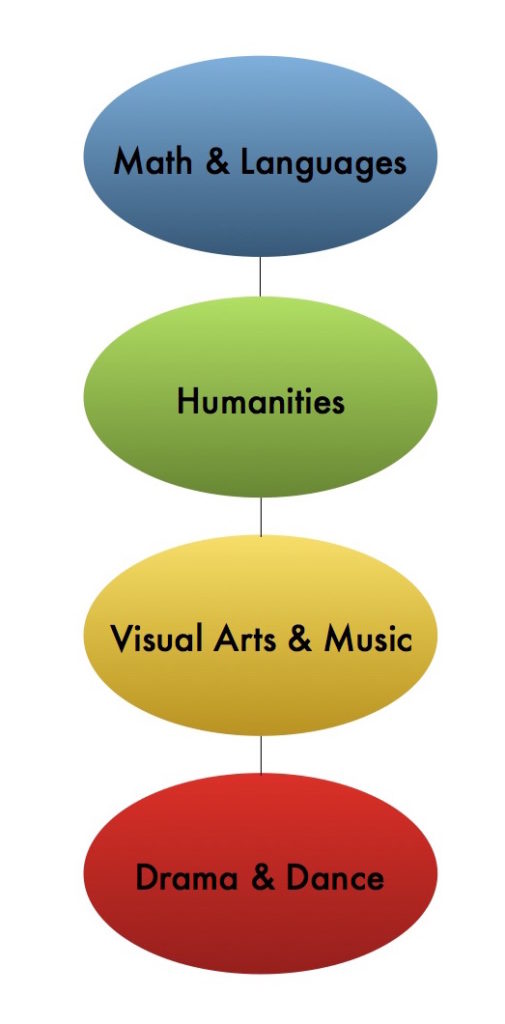

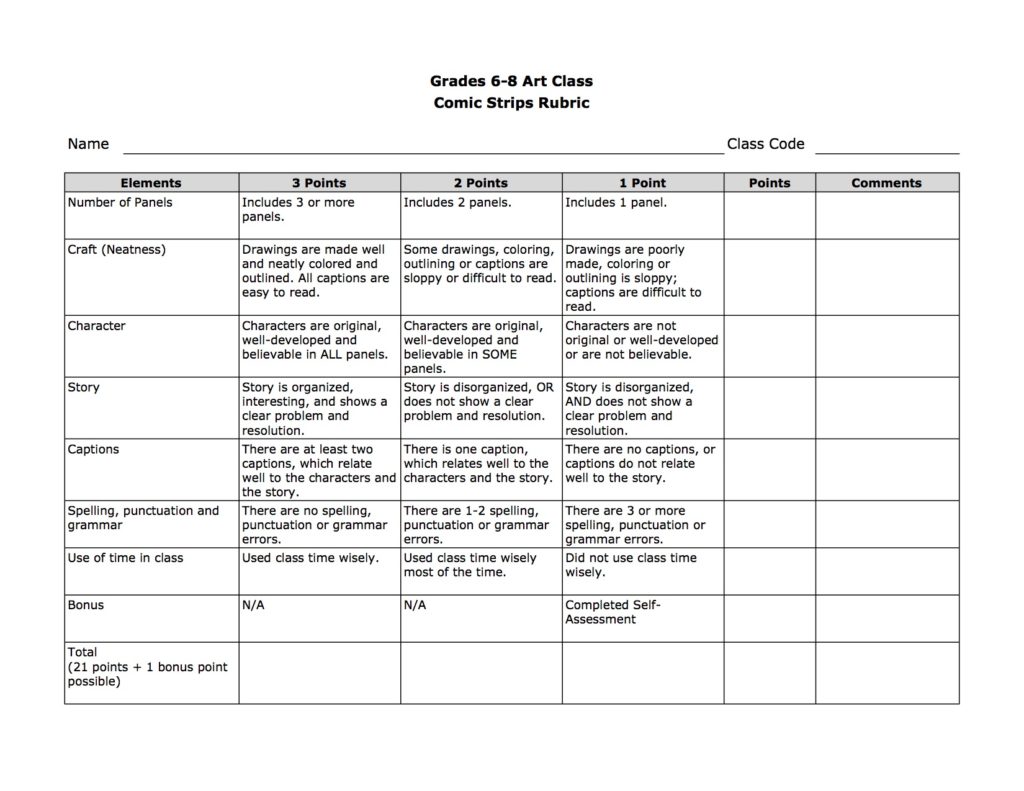

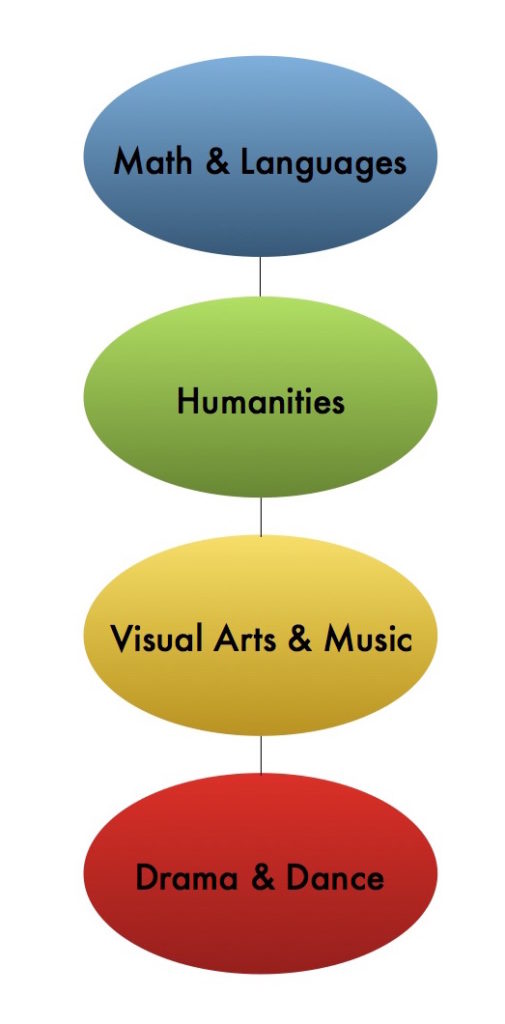

Hierarchy of Education Subjects, Based on Robinson, 2006

Teachers and administrators face increasing pressure from policymakers to meet benchmarks in proficiency and growth. The result is more time spent practicing test taking skills and less time spent in student-centered, inquiry-driven lessons. This narrow-minded focus on testing leads to narrow-minded thinking. The result? “Young Americans are being educated out of creativity” (Pomeroy, 2012).

We need creative students, though. Creativity is closely related to divergent thinking, the kind of right-brained thinking that leads to fresh ideas and new perspectives (Connor, Karmokar, & Whittington, 2015). When coupled with convergent thinking, the partnership produces the kind of innovation we are seeking (Maeda, 2012).

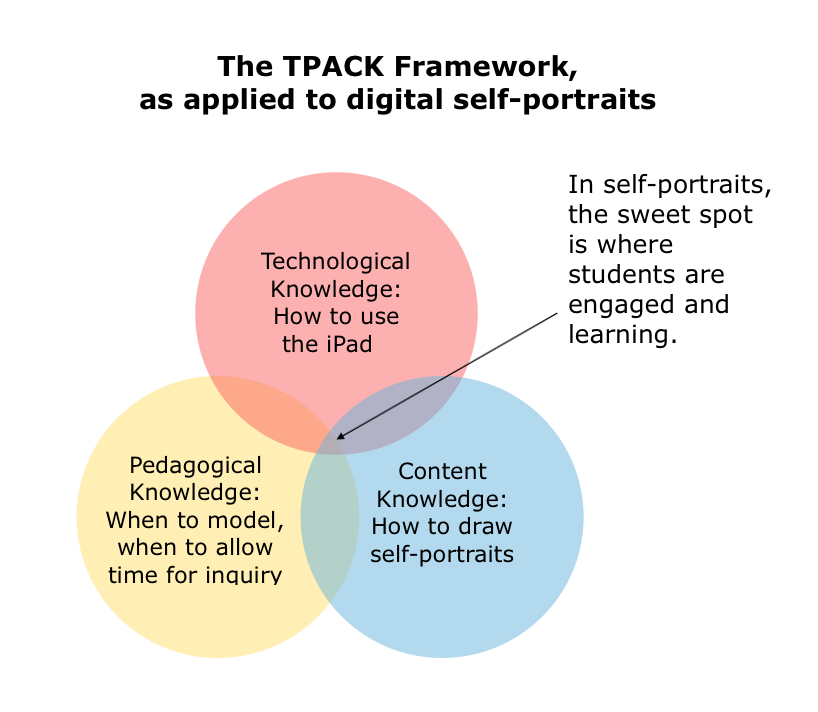

Creativity, “the process of coming up with original ideas that have value,” is now “as important in education as literacy” (Robinson, 2006). Unfortunately, the hierarchy in education places math and languages in a position of importance above the arts. This hierarchy denies the importance of the disciplines coming together. Yet where the different disciplines come together, like in STEAM education, is where creativity flourishes (Robinson, 2006).

Where Is STEAM’s Place if We’re Prepping for the Test?

Research shows that students who have a background in arts do better on standardized tests (Johnson et al., 2015). They are also leaders in entrepreneurship and inventing. Michigan State University researchers studied a group of MSU Honors College graduates. Those with arts exposure were more likely graduate from a STEM program and to own businesses or patents (Lawton, Schweitzer, LaMore, Roraback, & Root-Bernstein, 2013).

Artistic endeavors while young helped foster the kind of innovation that creates jobs and invigorates business. “So we better think about how we support artistic capacity, as well as science and math activity, so that we have these outcomes” (Lawton et al., 2013).

My Own Experience as a STEM / STEAM Educator

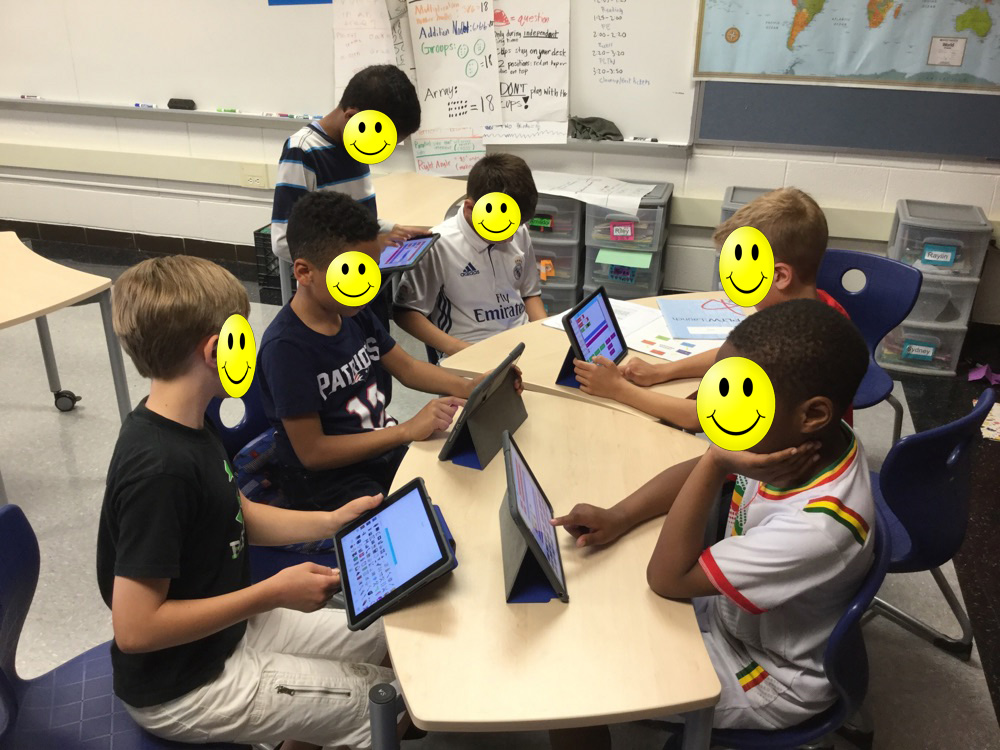

My current position is that of a K-5 STEM educator. In my role, I teach Project Lead The Way, a national curriculum with the aim of helping students learn 21st-century skills.

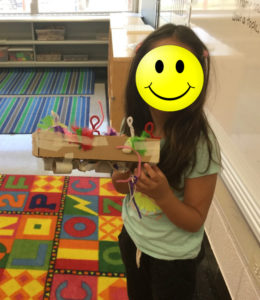

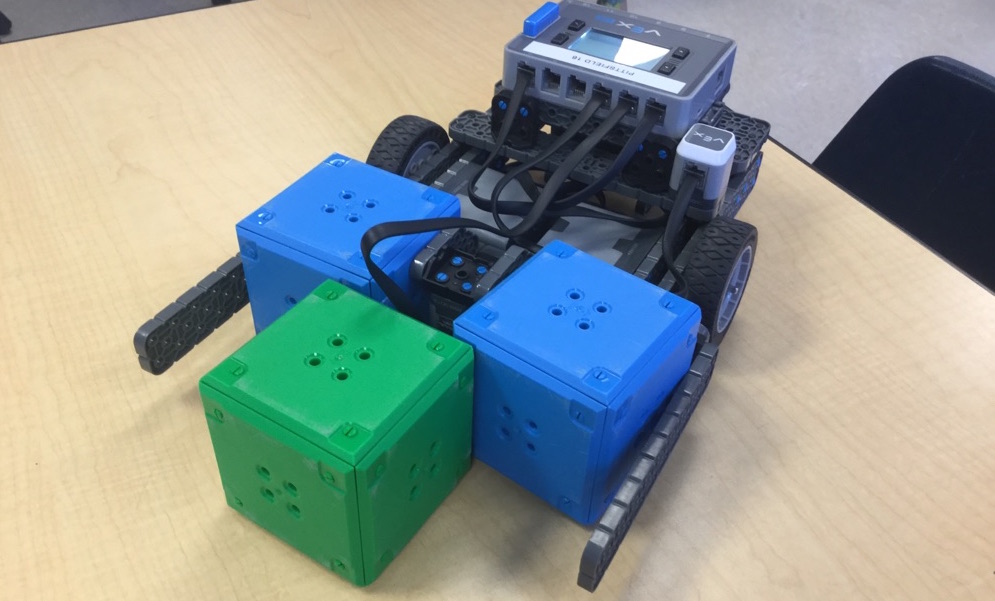

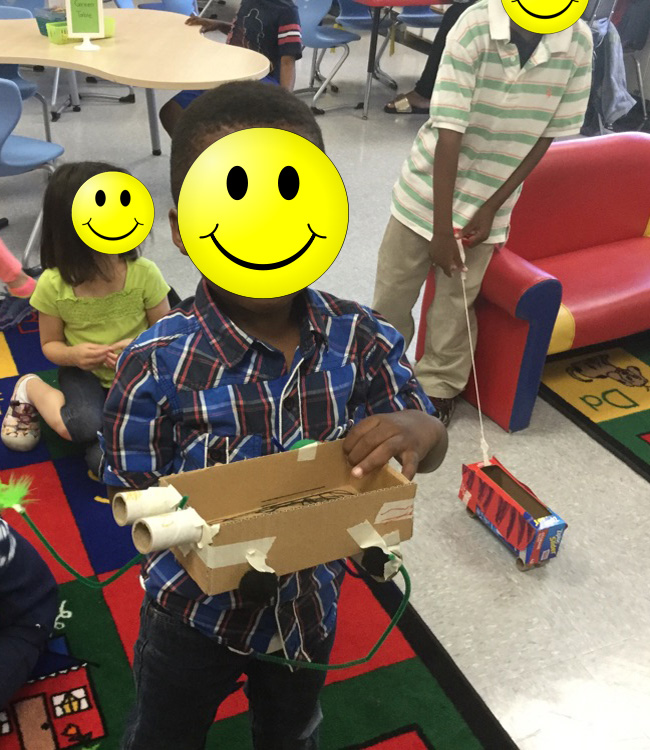

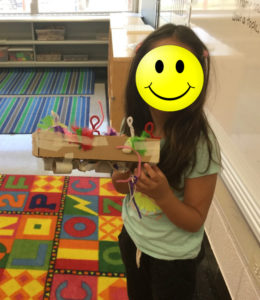

Last year, my kindergarteners learned about pushes and pulls. Their final project was to design and build a model that would move some blocks up a ramp. When I taught this unit at my first school during the first half of the year my students were successful. They all met the design challenge.

Last year, my kindergarteners learned about pushes and pulls. Their final project was to design and build a model that would move some blocks up a ramp. When I taught this unit at my first school during the first half of the year my students were successful. They all met the design challenge.

Before I taught at my second school, though, I had some time for reflection. I made a few simple additions to my supplies for building day. I brought along some feathers, pipe cleaners, pom poms, and cutoffs from cardboard tubes. I did not tell the students what they were to be used for and the design criteria remained the same: they were to build a model that could push or pull the blocks up the ramp.

The results were fantastic! Yes, they all moved their blocks up the ramp but they became inventors in the process. One student added a “monster sprayer” to her model. A second told me, “And this is a purse; you can carry it.” One of my young engineers told me, “It has a camera, and a hand for picking up rocks, and a hammer for smashing rocks.”

Looking Forward

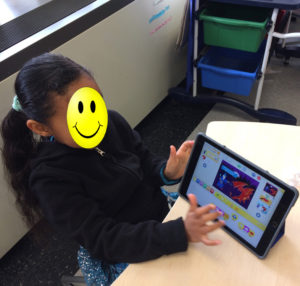

I feel privileged to be at the beautiful intersection of two STEAM disciplines. Trained as a Visual Arts Educator and earning a master’s in educational technology, I am in a position to infuse art into any STEM lesson that I can. If I am ever back in an art room, my goal will be to put technology into the hands of my art students. Either way, I look forward to educating tomorrow’s creative world changers.

References

Connor, A. M., Karmokar, S., & Whittington, C. (2015). From STEM to STEAM: Strategies for enhancing engineering & technology education. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy (iJEP), 5(2), 37-47. doi:10.3991/ijep.v5i2.4458

Johnson, L., Becker, S. A., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2015). NMC horizon report: 2015 K-12 edition. Austin, TX: The New Media Consortium.

Jolly, A. (2016, April 29). STEM vs. STEAM: Do the Arts Belong? Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/tm/articles/2014/11/18/ctq-jolly-stem-vs-steam.html

Lawton, J., Schweitzer, J., LaMore, R., Roraback, E., & Root-Bernstein, R. (2013, October 22). A young Picasso or Beethoven could be the next Edison. Retrieved from http://msutoday.msu.edu/news/2013/a-young-picasso-or-beethoven-could-be-the-next-edison/

Maeda, J. (2012, October 02). STEM to STEAM: Art in K-12 Is Key to Building a Strong Economy. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/stem-to-steam-strengthens-economy-john-maeda

Pomeroy, S. R. (2012, August 22). From STEM to STEAM: Science and Art Go Hand-in-Hand. Retrieved from https://www.yahoo.com/news/stem-steam-science-art-hand-hand-115600026.html

Robinson, K. (2006, February). Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity

STEM to STEAM. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://stemtosteam.org/

Images

All images and videos in this blog post were created by Sarah Van Loo.

Last year, my kindergarteners learned about pushes and pulls. Their final project was to design and build a model that would move some blocks up a ramp. When I taught this unit at my first school during the first half of the year my students were successful. They all met the design challenge.

Last year, my kindergarteners learned about pushes and pulls. Their final project was to design and build a model that would move some blocks up a ramp. When I taught this unit at my first school during the first half of the year my students were successful. They all met the design challenge.

My troubles weren’t over, however. When I tried to switch from the Uno to the LilyPad, I discovered that my LilyPad had gotten broken so I ordered a new one. Once it arrived, I was finally able to switch from the Uno to the LilyPad and got my LilyPad to light up the NeoPixels.

My troubles weren’t over, however. When I tried to switch from the Uno to the LilyPad, I discovered that my LilyPad had gotten broken so I ordered a new one. Once it arrived, I was finally able to switch from the Uno to the LilyPad and got my LilyPad to light up the NeoPixels.